Nicobobinus

Whimsy and political commentary from a Monty Python writer

So it turns out that just because a book was deeply important to you as a child, doesn’t mean the rest of the world remembers it, or knew it in the first place. In fact, to quote Rowlf the Dog, no one has heard of this ever-popular classic.

When I discovered that the copy of Nicobobinus that I read many many times growing up could no longer be found at my childhood home, I checked to see if I could get it at my library. Nope, no record of it in the city’s system. How about from one of my local bookstores? Struck out there too, even when I searched their website for books they could order for me. Finally I found a used copy on Amazon, and was able to begin one of the great does-it-hold-ups of my adult life.

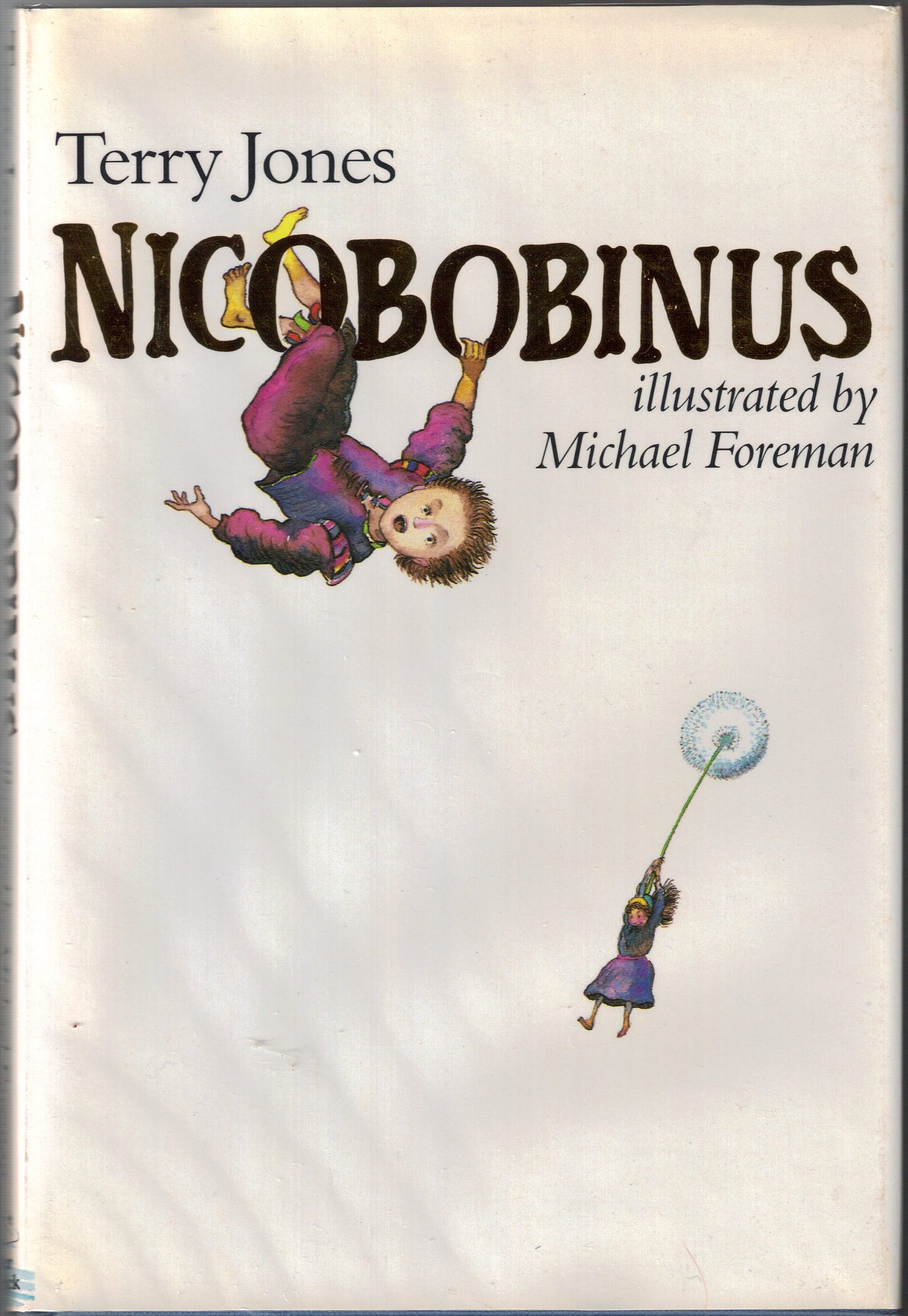

The Book: Nicobobinus

The Author: Terry Jones

The Illustrator: Michael Foreman

Length/Picture density: 170 pages, pictures every few pages (the hardcover has big, colorful illustrations, the paperback’s are more muted)

Before we get into this, a quick word about the author, because there’s a pretty good chance you are at least a little familiar with some of his work. Terry Jones was a founding member and lead writer for Monty Python’s Flying Circus, and directed Monty Python and the Holy Grail (with Graham Chapman), Life of Brian, and Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life. He also wrote an early draft of the screenplay of Labyrinth, the quirky, post-Muppet Show movie directed by Jim Henson, starring David Bowie, but apparently not much of his original script was in the final film. Jones was also a medieval historian and a political columnist (as well as a great opponent of the Iraq War).

So, what sort of children’s novel did that guy produce? One that’s deeply whimsical, full of thinly veiled political commentary, and a rollicking good time.

The story follows two Venetian best friends, Nicobobinus and Rosie through a series of adventures, all stemming from Nico attempting to pick fruit from a rich person’s garden, getting caught, and eventually having parts of his body turned to gold.

From there, he’s on a quest to find a cure for this magical malady, but they spend most of their time escaping pirates and other bad guys who want to dispose of him and keep his gold.

Jones uses this basic idea to direct his scorn at the rich, the powerful, and the Catholic Church, all of whom are rendered as greedy scallawags in this story.

But there’s a reason that I read this book, I don’t know, twenty or so times when I was growing up, and it wasn’t because I wanted another round of Jones dunking on hegemonic powers. It’s because the main duo, especially Rosie, are really likable, and the story is a ton of fun. Also, the Python-esque humor really worked for me. There is loads of adventure and action with a dash of magic thrown in. The bad guys are vile, but they are also ridiculous and generally not frightening.

There is some blood and violence, some of which I edited out while reading aloud, but it doesn’t take over the story. There are also phrases and terms that I didn’t understand because they were too old, British, or specific to boats (a fair chunk of the story happens at sea).

I’m guessing this one isn’t for everyone — the humor might not click for you, or the villains might be too gross, and every once in a while it gets a little hard to follow. The ending kind of goes off the rails too, as Jones tries to suddenly amp up the fantastical-ness of the story.

I find the whole thing silly and charming. I recommend giving it a shot, but it will take a little extra motivation to do so, because you’re not particularly likely to stumble on this one.

That said, I did stumble on a collection of Jones’ short stories, called “Fantastic Stories” also illustrated by Michael Foreman, in one of those book box libraries that are scattered around my city, and hopefully yours too.

These are also whimsical and political, a mix of fables, fairy tales, and cautionary tales. At the end of one of them he drops the pretense and calls out our societal nonchalance toward regular car accidents (a movement that finally seems to be gaining some momentum many years later). Nicobobinus and Rosie also make an appearance in the final story.

I liked these — there was enough there for me between Foreman’s illustrations, nostalgia, and the stories themselves — and Leo got into them too, asking for certain ones repeatedly. That said, if you’re going to go to some unusual lengths to track down either book, Nicobobinus is more worth your time.

Thanks for reading! Share, subscribe, or just say hi.